Launch p1

Species don’t survive by chance—they evolve and outcompete. The same is true in business. Organizations that fail to lead risk extinction, while those that adapt and advance thrive when their markets undergo tectonic shifts. Entrepreneurs and intrapreneurs behave like both genetic mutations and adaptive traits. As genetic mutations, they introduce bold, sometimes risky changes that can transform industries. As adaptive traits, they evolve processes, structures, and products to carve a niche that bestows a competitive edge. We do all of this in the name of innovation, but the selective forces are the same whether you’re in the C-suite or the rainforest. What can Darwin teach us about building future-ready businesses? What does being future-ready mean in the digital age of unrelenting hyperinnovation that brings great opportunity as well as existential risk? And how can leaders apply evolutionary principles to drive meaningful innovation? Let’s unpack…

In this series, I will focus mainly on the topics of innovation, entrepreneurship, and intrapreneurship, with a conceptual breakdown of what I refer to as systematized innovation followed by my first-hand experiences as an entre/intra-preneur. For context, my experience includes launching a number of successful entrepreneurial ventures (digital health and biotech startups), along with intrapreneurial ventures (an innovation lab for PerkinElmer and a precision medicine research program at the Harvard School of Public Health), and some in between (a premier global consortium for genomic newborn screening) so, although I will reference many published concepts, much of my writing will draw from personal accounts.

Anyway, let me “Quentin Tarantino” this and jump to the punchline before we get started: We humans are biological spinoffs of evolution, and our constructs such as ideas, products, and companies are held to the same forces that compel change. (Thanks a lot, Ch. Darwin!). Yes, we have anthropic words for what humans do, such as innovation and sales and engagement and ROI etc, but I will propose that these words have counterparts in nature, and the clearer that we see those parallels the more equipped that we will be at leveraging eons of evolution to guide our companies away from extinction.

What does living in a state of hyperinnovation mean? Simply put, it is when the speed and magnitude of new technological advancements flood us too quickly to track as individuals, and too multidimensionally to cope with as corporations. If you’re in a large corporation then you’ve likely heard the existential question of “What’s our AI strategy?”. Rest assured that the same corporations went through “What’s our data strategy?”, “What’s our mobile strategy?”, and “What’s our web strategy?”. (Venerable companies, such as Kongō Gumi, likely asked “What’s our electricity strategy?” at some point, but I digress.) In fact, I’d wager that this era of hyperinnovation started creeping up around the web strategy phase. Before that, companies (and society) had ample time to absorb new innovations. It took decades for the printing press to be adopted in the 15th century. It also took decades for electric light to become widespread once Thomas Edison created the first incandescent light bulb in the 19th century. It took decades for automobiles in the 19th century, and the same holds true for the airplane (20th century), mainframes (mid-1900’s), personal computers (mid-1900’s), and mobile phones (1970’s). Even in the digital world it took decades for email and the web browser, depending on whether you start counting when they were originally conceived or once a medium was established for broad adoption (ie the internet). Even artificial intelligence dates back to Alan Turing, at best, or to Aristotle, at worst.

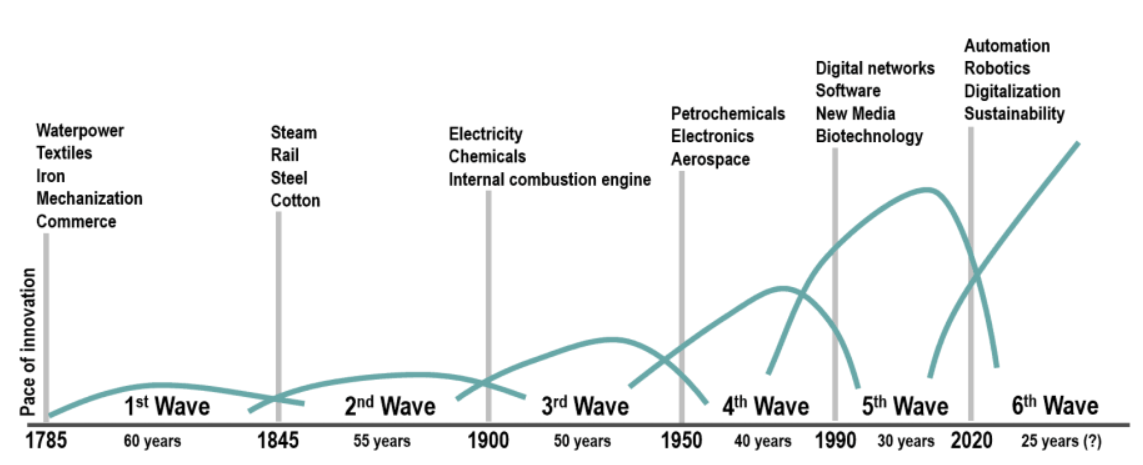

These long waves of innovation can be viewed in models such as those developed by economist Joseph Schumpeter (Figure 1), who coined the term “creative destruction” in 1942, and based some of his work on Nikolai Kondatriev’s hypothetical K-waves of economic cycles. I’m not here to argue the validity of these models, but they conveniently portray a conceptual representation of trends that have shaped our society.

Figure 1. Long waves of innovation. Source.

In order to mainstream, most of these innovation waves had requisite enablers (eg GPUs, Cloud and transformers for AI) and/or required a significant investment in infrastructure (electrical grids, roads, the www, etc), but when we look at the world of digital innovation today, most of the friction that stood in the way of prototyping and launching new ideas has been eliminated. (As a computer scientist, I have personally morphed from painstakingly creating my own software components on finicky servers under my desk, to digitally snapping together shrink-wrapped libraries that I freely download from the cloud.) If you’re a consumer at the head of the adoption curve, then you’re a kid in a toy store. If you’re commiserating with like-minded people through a rotary phone, then the odds are that you’re petrified. If you’re a corporation whose success depends on the digital world, however, then you simply must stay informed and engaged, if not leading altogether. Corporations should be acutely aware of the trends that influence their viability. Notwithstanding outliers such as Kongō Gumi, the average lifespan of public corporations has been on a downward trajectory over the past century (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Average company lifespan on S&P 500 Index in years. Source.

Disruption seems to be happening everywhere. It’s possible that we’re in that 6th wave of innovation depicted in Figure 1. It’s also worth noting that those waves of innovation do not reflect a singular innovation, but rather a cascade of multidisciplinary changes that were unlocked by a disruptive event. These are chain reactions that alter business, society and, even, our own role as creatures on earth. From an evolutionary perspective, I’d propose that much of this looks like transitions between genetic drift (periods of relative stability during which spontaneous mutations emerge in populations) and punctuated equilibrium (short spurts of rapid change that are bolstered by selective forces that lead to new states of fitness and speciation). And when we look at it from that perspective, there is a whole fossil record that can give us historical clues on how to survive and, possibly, thrive.

So let’s look at innovation. The word derives from the Latin verb innovare, meaning to renew. In simple terms, it means “the practical implementation of ideas that result in the introduction of new goods or services or improvement in offering goods or services”. One might even think about it in terms of “fitness”. When looked at it that way, an innovation differs from aimless creation by virtue of the elevated fitness that it renders to the owner of that invention. Survival of the fittest, right?

Natural Selection: the process whereby organisms better adapted to their environment tend to survive and produce more offspring.

To draw distinctions from a natural system that is seemingly unintentional and unpredictable, let us consider an alternative form:

unNatural Selection: the process whereby organisms organizations better adapted to their environment markets tend to survive thrive and produce more offspring impact*.

Let the lateral thinking begin!

Note that the main distinction that I made between natural selection and unnatural selection pivoted on intentionality and predictability. Sure, sometimes innovations happen almost spontaneously, but I’d say that those are exceptions and, unless you’re in a position to acquire said innovations, spontaneous innovations are impractical to corporate strategy when they rely on the equivalent of brownian motion. A logical question might then be “can we systematize innovation so that it’s intentional and predictable?”. Well, given that we are mapping a natural phenomena to a conscious and thinking species that is capable of shaping the natural world to its own interests, I’d say that there is certainly a lot that we can do to stimulate creativity, steer ideas, test hypotheses, and optimize for success. In fact, I’d bet that most serial innovators have some methodologies that they like to follow for repeatable success, whether they do so on their own (as entrepreneurs) or within a larger organization (as intrapreneurs). Next we will consider some principles that are common to all environments, and then we will turn to some of the distinctions that can make a world of difference depending on which preneur card you carry.

*When I first coined the term I used the word “returns” instead of “impact”, but since then I have founded university research programs and international genomics consortia, which measure success differently from financial returns.